Numbers and Naturalness, part 3

After we learned a bit about p-adic numbers, it's about time to get to the naturalness. Let me just discuss some hypotheses about the structure of the world we live in

Assume we live in the world that made of p-adic numbers. Yep, instead of $\mathbb{R}^3$, for instance we could live in $\mathbb{Z}_p^3$. Sounds crazy, because we are so accustomed to thinking about lines, axes and so on which in our geometrical imagination are tightly connected with the real numbers.

But can we treat it (our geometrical imagination) as the argument to reject the hypothesis of p-adic space? Well, we can't. There are many examples in which our geometrical intuition fails to discover the real world (non-Euclidean geometry is probably the most vivid one).

But there is another argument.

Let's look at special relativity theory.

The key moment is we have spacetime instead of time separately and space separately. The space and the time

have similar nature, but the time can't be p-adic variable, because it should be ordered (otherwise we can't talk

about causality principle).

To be more precise, the elements of spacetime are partially ordered, but this ordering is based on comparison distance in Minkowski space (which is obtained using arithmetic operations) and zero. Anyway, ordering is needed, and we don't have it in p-adic numbers.

I wrote much about simplicity of real numbers and the simplicity of their definition. It's about time to talk about why they can't substitute real numbers (which doesn't imply they are useless).

- Real numbers do not depend on the radix you use, and this is essential. If I state that p-adic numbers should be used in some physical theory, I should also name the prime p. 2? 3? 5? I can't see any reason to prefer one number to another. The real numbers are the only.

- Ordering once again. The first step in theoretical physics is least action principle, which states that some function (action, helps Captain the Obvious) should be (locally) minimal on the solution trajectory. If you don't have ordering, the assertion like this cannot be stated.

- Every time we talk about optimization, we mean real values. The optimization criteria result should be in

ordered field, and, based on the optimization theory, it's much better if the set or results is complete

(otherwise there is no guarantee that solution exist).

How many fields are there that are both ordered and complete?

The answer is known: there is only one. It is $\mathbb{R}$

(but note: the result doesn't have to belong to some field)

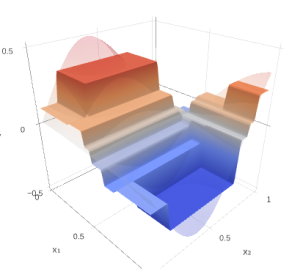

Gradient boosting

Gradient boosting  Hamiltonian MC

Hamiltonian MC  Gradient boosting

Gradient boosting  Reconstructing pictures

Reconstructing pictures  Neural Networks

Neural Networks